|

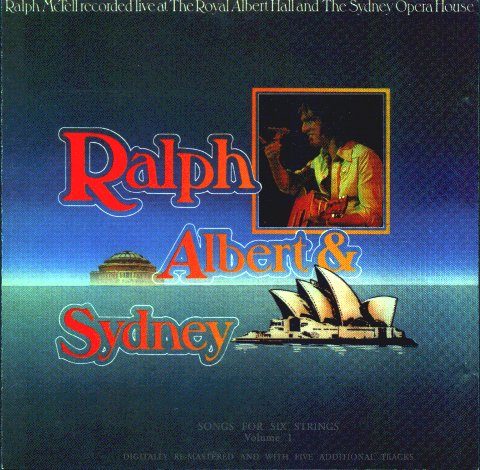

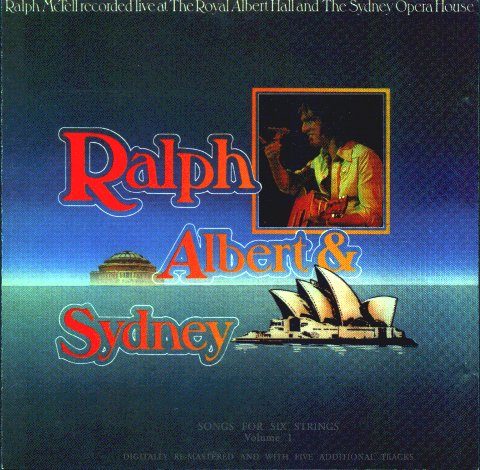

RALPH, ALBERT & SYDNEY

MUSIC

PRESS

Ralph McTell – The Soldier Who Didn’t Want

To Be A Hero

By Rosalind Russell

Disc & Music Echo 11 September

1971

“Two days after joining the army it dawned on me that it wasn’t a game, and

that I was in a killer force…it was a traumatic experience”

Ralph McTell is too sincere for his own good – at least he would be if he was

seeking fame and fortune in a business where sincerity doesn’t count for much.

But not being a bread head and asking no more than understanding from his

audiences, the trappings of the pop business hold little interest for him.

He could be excused if he did want money, because it’s a commodity that

hasn’t come easy in his family.

Born

26 years ago in Farnborough, Kent, Ralph lived with his mother and younger

brother Bruce. His

father disappeared early on in Ralph’s life, leaving Mrs McTell1 to

cope with two young sons. Although

Ralph didn’t realise it at the time, his father’s action affected his life

quite considerably. He

had a very happy childhood, and felt that the family unit of three was complete,

but can look back on it now and see the responsibility he felt towards his

mother.

“Your

role in that relationship must be different because of your responsibility to

one parent and you realise very well that one parent has given up a lot to look

after you. It’s

very easy to dump kids in a home and if one parent decides to stick with the

kids, that’s something of a sacrifice.

If you have two parents, you don’t feel, when you leave home, that

you’re doing a bad thing. Actually

it’s surprising how many people in the music business come from broken homes.

“I

think they are essentially creative as a result.

I think that being brought up by one parent, and that being my mother, I

became more sensitive in my formative years.

I don’t think people from broken homes are consciously attracted to the

business, but being insecure brings out a creativity.”

Ralph’s

creativity wasn’t doing much in those earlier days – he rapidly began to

lose interest in learning. People

had said that he would go far and that brother Bruce would have some catching up

to do, but it turned out that Bruce streaked ahead academically and is now a

lecturer in Sociology. Ralph

stresses that his dropping out was not a result of being left fatherless.

Later on he even wrote a song about how happy he has been with his small

family. “Daddy’s

Here” is an understanding of the problems his mother may have had, and shows

that they are none the worse for that.

The song is included on Ralph’s first album2, “Spiral

Staircase”

Usually

a modest person, who speaks when there is something special to say, Ralph was

uneasy at expressing so many of his views in what might be interpreted as words

from a self styled prophet – as many artists think they may be.

But there are no castles in Spain for him.

He sits back on the sofa in his manager’s London office, playing lap

host to two small pugs, Nelson and Henry (papa and junior respectively) who

belong to manager Jo Lustig.

They go to sleep and snore loudly into the tape recorder.

Ralph’s

talent in music and songwriting didn’t begin to develop until he had done a

fair amount of growing and living.

He found what he thought would be an easy way of leaving home without

causing too much heartbreak for his mum, and went into the Army at 15 years old.

He had been a cadet at school, playing soldiers and going off to camps.

He found that the real thing was quite a different story.

“I

thought that joining the Army would be a secure thing.

It meant that I would be looked after.

It was one of the easiest things in the world to join the Army, and one

of the hardest to get out of.

“I

was out again before I was 16.

It was a short stay and a memorable one.

It was very traumatic, actually, the two things coming together –

leaving home and thinking I was going to make it.

It was amazing too that so many kids in the Army – the boy soldiers –

seemed to come from broken home backgrounds, or Borstal, or were illegitimate

kids. In other words,

they were the real under-privileged, the ones who had got a chip on their

shoulders. They were

the ones that make good soldiers, because they were at odds with the world

anyway.”

Disgusting

About two days after joining up, it dawned on Ralph that it wasn’t a game, and

that he’d joined a killer force.

He also realised that he wasn’t as brave as he thought he was – the

training and assault courses held a terror for him that they didn’t for some

of the other kids. He

wouldn’t recommend the Army as a bed of inspiration, but agrees that it

probably helped him to grow up with more mature ideas and a better understanding

of people than he would otherwise have had.

“After

13 weeks of what they call basic training, but what is breaking your spirit –

at least that’s what it was for me – the leaders have emerged and the others

are knocked into shape to go on with their proper units.

I was in what is essentially a killing unit, the infantry is known as the

teeth and arms of the Army. I

was told that I’d be able to carry on with my education, but that was a joke. A

lot of the kids couldn’t read or write.

“We

got £2 a week wages and £1 of that went on cleaning equipment, and I also got

some of the most disgusting food I’ve ever seen presented to anyone in my

life. The discipline

was ruthless.”

A

sharp dose of discipline was the final straw for McTell.

He received a whack from a pace stick – the rod used to mark out the

length of a pace – which nearly broke his wrist.

Despite exhortations from some of his family to let stay in because “it

would make a man of him”, his mother borrowed £50 and bought him out.

His departure is full of memories of other lads who couldn’t take that

way out, and tried to kill themselves instead.

Although

his stand has changed radically to anti-war, he is quick to jump to the defence

of anyone who dismisses soldiers as mindless robots.

“A

lot of people might think this is strange, but I still get very moved by parades

of soldiers. They

aren’t toy soldiers now. Even

the guards are fighting in Ireland.

There is something about the anonymous ranks of brown uniforms that is

moving, because there are human beings among that lot, whom we allow to be

brainwashed into being machines.

We also allow the disgusting process of letting a 15-year-old boy sign

away the nine best years of his life.

“There

were so many boys from Scotland there – a whole company full of them.

“They

are exploited to the maximum because people fail to have enough sympathy to see

what forces a guy into such a situation, to go out and be a professional killer,

whatever the reason.

“The

cats who scream about revolution and such, should realise that the soldiers are

just as under-privileged as they are – that’s a specific reference to

Northern Ireland. These

guys have more in common with the people, but they don’t realise it because

they are being used. About

the third day I was in, it suddenly dawned on me that I might get shot getting

off a boat somewhere.”

The

under-privileged and the lonely have always been somewhere in Ralph’s list of

lost causes. He has a

penchant for looking after and protecting lame ducks, and the Army gave him some

first-hand experience.

When

he got out, he went to a further education college, to get some “A” levels.

He didn’t stay very long, partly because he didn’t feel at home with

most of the students there. Another

McTell bogey raised its head, and he found that class barriers were still very

much in evidence. His

Croydon accent stood out from some of the middle-class voices around and he was

made to feel uncomfortable. He

did, however, begin to develop his interest in music there, and at 17 began

learning to play the guitar seriously.

He also began to draw, and passed an “A” level in Art.

It

was listening to an album by American country/folk singer Jack Elliott –

“Jack Takes The Floor” – which really caught Ralph’s attention.

He heard authentic versions of “Bed Bug Blues”, “Cocaine” and

then turned to Woody Guthrie.

“It

was then that I picked up the guitar and worked at it.

I decided I could become a busker like Wizz Jones and a few others that

were around then. A

few guys were busking at the weekends and a few stories actually filtered

through about people who had even left the country with their guitars.

That was really something then.

Hardly anyone was doing it – that was in 1959.”

The

romance of bumming off to Europe with a guitar appealed to the lad from Croydon,

where his family was then living, and came as a reaction to the institution-like

confines of the Army. He

met another guy who could play guitar, but didn’t learn anything from him.

“He

used to say that he’d had to pick it all up himself and so I could too.

He used to play with his back to me, which was bizarre!”

Immoral

Despite their differences, they set off for France, and later travelled to

Holland and Germany. It

was the first of quite a few trips abroad.

Ralph would come back for a while, and get a job on a building site until

he had enough to go off again.

During

one stay in Germany, sleeping in cold doorways and lack of food made him very

ill. He travelled

down to France and was shipped home by the British Consul.

In France, he and his companion spent several nights in jail and were

lucky to come off lightly. The

usual procedure by the police there was to take the guitar and smash it off the

nearest wall – to make sure the busker didn’t busk again.

It was well for Ralph he was nimble enough to dodge the heavies.

On

his last trip to France he met his Norwegian wife, Nanna.

She was one of two girls collecting money for another busker, who lent

her to Ralph to do his collecting.

She was studying at university in Paris but came back with Ralph,

married, and is now mum to their two children, Sam and Leah.

But

before he married, Ralph managed to make it to Greece, where he’d always

wanted to go. He

busked there with a guy he met on the road and spent a really good time there.

They were thrown out of one town four times for busking.

Each time they came up before the long-suffering Chief of Police, he told

them, “It’s the last time lads.

It’s illegal, you’ll have to go inside,” so they didn’t push

their luck after the fourth bust.

“I

went to Turkey from there. That

was really being on your uppers.

It was sort of immoral taking money from the Turks who are incredibly

deprived people. We’d

work for three hours and end up with perhaps a quarter of the amount we’d earn

in Venice in 15 minutes. In

Turkey, people would gather round at the novel sight of a European begging,

because that’s what it was.

“But

in Paris we became really well known to the cinema queues, and when the police

came to hussle us the crowd used to gather round and boo and hiss at the

cops!”

In

Paris, Ralph was invited to audition for the job as guitarist to Antoine – at

that time billed at the French Bob Dylan. Antoine, however, couldn’t play

guitar – he mimed and had three guys in evening dress sitting behind him,

supposedly as a backing. The

only one playing guitar was Ralph.

He played for him at the Olympia for three weeks at about £4.50 a night,

no questions asked!

“I

was worried because I wanted it all to be above board – I didn’t want to get

busted for working without a permit and de Gaulle was tightening up then –

kicking all the bums out.

“The

best thing that happened to me was that I saw Francoise Hardy, just standing

there. She’d come

along with Juliette Greco and was just standing in the audience.

Antoine was playing to sell-out audiences.

But Francoise Hardy was different to what I thought she was from her

pictures.”

Ralph

also had to tune Antoine’s guitar for him to strum, but as the French concert

pitch is different from everyone else’s, the guitars, the harmonica and

orchestra were all quarter keys apart.

But the audience didn’t seem to notice, and Antoine got rave reviews in

the French papers.

On

his return to England, Ralph was asked to go to Cornwall with Wizz Jones, whom

he’d always admired, to play guitar with him.

In Cornwall, he began to think seriously of doing something creative and

stable, and finally decided on applying for a place in teacher training college.

At least this would still provide the opportunity to be creative.

He also had his wife and soon a baby, to think about.

His

own background being so one-sided, Ralph made sure, and is still conscious of

it, that he would be with his family as often as he could.

He also began writing more songs then, becoming more aware of the social

problems around him, and facing up to what was going on among under-privileged

people – a thought which he’d more or less hidden with his memories of the

Army.

“Streets

of London” was one of his first songs and probably his best known.

It’s on both of his albums here and has been released as a single in

the States, preceding his forthcoming visit.

It has also been recorded by many artists, and the sheet music made the

charts and stayed there for a couple of months.

So

it’s odd that the song which has taken him far is the one he didn’t think

was any good. It was

only after much persuasion that he added it to his album.

From that one song you can learn a lot about Ralph’s environment.

A country person couldn’t have written a song like it, and by the same

token, a city person can have more appreciation of a beautiful dawn than the

farmer who sees it so often that he takes it for granted.

In

the song, he shows you the poor and lonely of the city, and loneliness is

something Ralph McTell cares about.

Looking back on his songs he finds that many of them are about the

problem, and from letters he receives, it shows that he has communicated to

people in his audiences who understand it too.

A headmaster wrote to say that he played the album to his children in a

village, because they had no conception of what it must be like to be lonely,

and someone else – a teacher – had his class paint pictures from their

imaginations after hearing the album.

This is where Ralph McTell finds his rewards.

“I

acknowledge my debt to “Streets of London” but I’m looking forward very

much to the day when I don’t have to sing it.

I find that the song has preceded me wherever I go.

Everyone already knows it.”

Confession

He will, however, have to sing it during his trip to the States.

Among other dates, he will be playing at the Bitter End in New York and

the Troubadour in L.A. He’s

also doing a “Frost Over America” TV appearance.

Quite apart from this being his first appearance there, his main fear is

of flying to the States.

“It’s

a drag but I know there are lots of people in this business who are the same.

One of the reasons Alan Price left The Animals was that he didn’t like

flying. The prospect

of spending seven hours in the air is very heavy.

I don’t mind propeller planes – planes with a visible means of

support. It’s the

jets I don’t like. I

know there’s a propeller there, it’s only because I can’t see it that I

worry. I feel as

though I’m in a sealed bullet, blindly flying through the air with no control

over it.

“I’m

not crazy about the idea of death, but I’ve been through all that.

Somehow it’s the impersonal business of an aeroplane crash.

There’s no chance of surviving if anything goes wrong.

It’s a bad confession to make, especially after writing a song like

“The Ferryman” which is centred round the ideas of Buddhism.”

Ralph

began to write more songs while he was at teacher training college and through

an introduction to someone at Essex Music, made a recording deal with

Transatlantic and left the college.

He thinks that if he hadn’t left, he might have been kicked out anyway.

He got into the college largely through the influence of a more radical

person on the college board.

He admitted to Ralph later that he liked to bring in enough radical

thinkers just to act as a stimulus, so that the students wouldn’t become

complacent about political and social affairs.

After Ralph left the college, most of the radicals were removed.

But

Ralph McTell is still a radical, although he worries about stepping on

people’s toes in his beliefs.

Still fighting for his soldiers, he points out that nothing has changed

– you always hear about the lads being shot in Ireland, but it’s not often

an officer gets caught in the line of fire.

McTell

puts them all in his line of fire, but you won’t hear him preach it from his

platform. He

doesn’t usually explain his songs either.

If you listen, in an audience, or to his albums, Ralph McTell says it

all.

Ed’s

notes:

1. McTell is

Ralph’s adopted surname. His

mother is Mrs May.

2. Ralph’s first

album was “Eight Frames A Second”

MJ

BACK

TO INDEX

MUSIC

PRESS

McTELL: LIVING ON THE STREETS OF LONDON?

Beat Instrumental

January 1973

Ralph McTell hadn't played a guitar before he was seventeen years

old. The thing that inspired him to actually pick one up was a record by

Jack Elliot, played to him by a friend at college.

'It was something about the roughness', recalls McTell, 'that made me

want to be able to do the same. There was an obvious joy and enthusiasm

there. Skiffle music was very popular at the

time and to me Elliot's guitar playing had the same quality in that it

was rough and ready."

TRIAL AND ERROR

One of the first songs that McTell learnt to play was Elliot's San

Francisco Bay Blues. As he'd never had any musical education in his life

he decided to be his own tutor and develop a style out of trial and

error. 'It's the only bit of maths I've ever done in my life', he

remembers. 'I worked out all the chords through a process of

elimination.'

For the next four years McTell only worked with material written by

other artists. For a part of that time he was 'on the road' travelling

through the continent with his guitar. At the time hitch-hiking and

bumming around weren't the popular activities that they have since

become.

In fact it's only through the pioneering work of his generation that

this lifestyle has become so commonplace today.

LESS EXCITING

McTell feels that because a lot of the freedom that the beat generation

fought for has come to pass, it's made things a lot less exciting for

the youth of today. At one time, he remembered, hitching to India was

just a far-out dream that a few eccentrics would actually go out and

achieve. Now it's every other resident of Ladbroke Grove and the

immensity of the challenge is somewhat reduced. The fun in the early

sixties', recalls McTell, 'was that you were persecuted for what you

were. Now you can have shoulder length hair and work in a bank.' He

feels that there's so much freedom around in society today that the very

need to rebel is well accommodated within it's structure. 'In order to

appreciate freedom you have to be a prisoner. It's like in order to

improvise you have to have rules.'

PESSIMISM

He blames his attitudes on being old (27) but he's admittedly very

pessimistic about life today in spite of the fact that his generation's

ideals have become a way of life. The freedom to f-ck your life up and

abuse your body - I'm not into that.

Today people are going for the over-sensational . . simulated

excitement. Yes, I admit I do look back a lot. I'd like to be optimistic

about the future but it's hard.'

FINANCE

Almost synonymous with the name of Ralph McTell is the song Streets of

London which he is only too willing to admit has helped him quite a lot

financially. The song is now regarded as a 'standard' on the folk scene

and has been recorded by sixteen other artists. Many critics have

pointed out the similarities between it and Meet Me On The Corner by

Lindisfarne. The similarity has also struck McTell but he couldn't care

less . . . there are only a limited amount of chord progressions around!

The tune for Streets Of London was written while he was in Paris and the

song was written for a friend. "I owe quite a good deal to that

song', he says.

Ralph McTell has now signed a record contract with Warner Reprise and

along with the careful guidance of his manager, Joe Lustig, this should

see him permanently fixed on the concert circuit. 'I did small clubs for

a long time/ says McTell.

Lustig is quick to point out that the fact Ralph is sticking to concerts

rather than clubs is for physical rather than economical reasons.

Apparently they just can't contain a McTell following in a dingy cellar

any longer.

BACK

TO INDEX

MUSIC

PRESS

RALPH McTELL – Royal Albert

Hall

Review By Roy Hill

Publication Not Known

1974

Singer/composer, Ralph McTell can hardly be classed as a superstar

and yet he manages to pack ‘em in.

What I like about his music is that it can be absorbed without having to really

listen hard. McTell delivers his

songs with such ease that you get right in there with him.

At the Royal Albert Hall his new album Easy, featured strongly in his act with

Summer Lightning, Zig Zag Line (a song about McTell and his little lad), Sweet

Mystery and Maddy Dances (dedicated to Steeleye Span’s Maddy Prior) all

delighting the audience. Somewhere

in the concert there just had to be Zimmerman Blues and the obvious happened for

his encore. Streets of London was

what everyone wanted and it was what they got, even yours truly sang along.

Another stamping of feet brought McTell and his bass accompaniment, Danny

Thompson, back on but alas all good things must come to an end.

Supporting McTell was the very beautiful sound of Prelude who received a

fantastic reception and capped their fine performance with After the Goldrush.

BACK

TO INDEX

MUSIC

PRESS

Disc

21 December 1974

RALPH McTELL : FROM THE STREETS TO STARDOM

By Ray Fox-Cumming

STREETS OF LONDON, they say, is such a sad song, but it isn’t at all,

believe me. To the bedsit brigade

– in London or any other British city – it has become an anthem of hope,

telling you, no matter how hard you feel the world has treated you, that you are

better off than the guy from the seaman’s mission or the lady who carries her

world in two plastic bags.

But

what of the down-and-outs of London? Is

it, to them, a statement informing them of their ultimate wretchedness?

Not

at all according to Mr McTell: “If you think people who sleep out in London

are hard done by, you should see the same people in Paris.

If they lie out in the streets, people don’t give a damn, they just

walk over them. You’d never

believe it, but when they lie over the vents in the pavement where the warm air

comes up, they have to sleep with their shoes under their heads.

If they leave them on their feet, people come along at night, undo the

laces and take them away.”

Streets of London was written partly in Paris and partly in London,

but it’s not a George Orwell type story of “Down And Out In Paris And

London”. McTell says that, while

not on his beam ends, he wasn’t exactly wealthy in those days, but the song

wasn’t written as a piece of advice to himself.

“It was written for a friend.”

The

song was penned some eight years ago and for two years after that for some

inexplicable reason, McTell chose to offer it to his folksinger friends rather

than record it himself.

Eventually

he did get around to doing it in the studio and it has appeared twice on albums

of Ralph’s apart from countless cover versions both on singles and albums, but

until now Ralph has been prevented from putting the song out as a single for

contractual reasons.

At

one point last year he became so embittered over his lack of freedom with the

song that he vowed never to sing it onstage again: “But in the end in my whole

career I’ve only got through six concerts without doing it…” and then

there were complaints.

Now

that the song is a hit for him, Ralph still doesn’t reckon himself as a

singles artist and almost seems naïve enough to believe that his record company

won’t expect a follow-up. Fortunately

though, he’s not in the same position as someone like Peter Sarstedt, who

found himself in the position of having a classic first hit that he could never

follow.

For

years Ralph has been one of the very few folk artists who could sell out

anywhere they chose to play without the bonus of a hit.

“If there are new fans,” he says modestly, “I don’t know where

they are going to go. We’re

pretty full most places already.” Pretty

full? Nonsense, they’re full –

to the brim.

In

all his career so far, Ralph has gone out as a solo artist with perhaps one

extra musician to help him out now and again, but now he plans to fill out his

concert sound with a group.

“I’ll

be touring here again in February and for the first time I’ll be using a

group.” He won’t say precisely

what the group will comprise, because he’s not yet sure himself, but already

rehearsals have been going on for a couple of weeks with a basic four-piece

outfit and Ralph says he’s surprised how well his songs have adapted to the

bigger sound.

Last

week, for the first time in his lengthy career, he did “Top Of The Pops”.

“I was scared still but as a whole experience I enjoyed it.”

In

a way he was fortunate, because the particular edition of the programme he

appeared on was a goodie – including such worthy musicians as Elton John,

Status Quo and others. It’s nice he was able to feel at home. After such a long haul to get there (whether he wanted it or

not) he deserved it.

BACK TO INDEX

MUSIC

PRESS

Ralph

McTell – Take It Easy But Take It

Article from Zig Zag Magazine Vol 4 No 2

Date of publication not known - circa 1974

By Fraser Massey

If that title

means anything to you at all, it’s either because you’re a Woody Guthrie

fan, or you’ve been to a Ralph McTell concert. The words are Woody’s, often

quoted by Ralph at the end of a gig, where others would say “Peace, love and

the spirit of Woodstock” or “I gotta go”.

However, this is not an article on the farewells of the famous, nor is it

about the great Mr Guthrie-it’s an attempt to unravel the musical career of

Ralph McTell.

But, we can’t start at the beginning, Ralph is more than fed up with talking

about his early days and influences, having told it all so many times to the

British music press. Anyway, he

considers that “the story of what you do before you record anything can be

glossed over in a couple of lines normally”.

If you try that in Ralph’s case it reads something like – he busked

his way across Europe, from London to Ankara and back, making his headquarters

in Paris where he wrote his first song, underwent a great deal of influences and

made a hell of a lot of friends.

ZZ: Why did you pick the name

McTell?

RM: I didn’t actually. I had just come back from Paris, I was about nineteen at the

time and I was working with Wizz Jones down in Cornwall. He wanted some unusual name on the posters and I was playing

a lot of Blind Willie stuff at the time. So

they called me Ralph McTell and the name stuck.

ZZ: What sort of places were you playing in when you got the recording

contract?

RM: Well I was just very amateur at the time, playing

in folk clubs and hotels. I had a

jug band at the time. Then I went

to college where I actually got the contract.

ZZ: Who was in this band of yours?

RM: The personnel used to change a lot.

There was Mick Bennett, he’s still around.

We used to call him ‘Whispering Mick’.

He was in Clive Palmer’s band, you know C.O.B.

Bob Strawbridge was in prison last time I heard of him.

Mac MacGann, he used to have a band called the Levee-breakers which

Beverly Martyn used to sing with, you know, John’s wife.

That’s about all you would know.

ZZ: Pete Berryman?

RM: Oh Henry VIII on jug of course.

Pete joined just before I left actually and took over the band in

Cornwall. I had to leave to go to

college.

ZZ: And they became the Famous Jug Band?

RM: Eventually, yes. Pete and Henry and then Clive joined them.

The First Two Albums and Chasing That Song Around The Country

In 1968 Ralph recorded his first album, ‘Eight Frames A Second’ for

Transatlantic. The jug band make an

appearance on a couple of tracks. There

are thirteen tracks in all; nine of Ralph’s compositions, one traditional

song, a rag by Blind Blake - all of which are beautiful.

The other two tracks should never have been put out.

Tim Rose’s ‘Morning Dew’ is completely destroyed by Tony

Visconti’s attempt to emulate the Phil Spector sound, the other track,

‘Granny Takes A Trip’, credited to Bowyer/Beard, sounds similar to all those

early Bowie tracks they keep on re-issuing.

The whole thing was packaged in one of the worst covers I have ever seen.

Nonetheless, the album is well worth a listen, if you can get hold of it.

The next year saw the release of the ‘Spiral Staircase’ album which had a

superb cover, again featured the jug band, had fewer production errors (if at

times a little too much orchestra) and of course featured that song ‘Streets

of London’.

RM: I was totally bewildered by it all when I made

the first album. It was Gus’s

first production, Gus Dudgeon who has since become very famous.

He was as confused as I was – we did it in Pye studios.

It was Tony Visconti’s first arranging job on an album.

I had a bit of a fight to get Gus to let me play my own guitar on it.

There was the usual clutch of session men who I was totally in awe of.

We made the usual mistakes, no, I made the usual mistakes that people do

on their first albums. There’s a

lot of tracks that I’m not happy with. I

mean the songs are alright, I don’t dislike any of the songs I’ve written,

but I think some of them could have been approached better.

ZZ: Was it your choice of material for the album?

RM: No, not entirely, I would have put much more

blues and stuff on it. I wanted to

do an album like Bert Jansch’s first album.

I know our styles are entirely different, but I would have thought guitar

and voice would be fine. Transatlantic

had this idea of making me a pop star or something.

It was their idea that I had the haircut as well.

In fact Nat Joseph gave me twelve quid to get some decent gear for the

photograph on the cover of the album. That’s

why I was wearing that Marks and Spencer pullover.

I did the haircut myself with a razor blade and a comb.

Lots of people think I look like a boxer or something on the front.

Also there were a couple of songs on there I wasn’t too happy with.

I originally recorded Leonard Cohen’s ‘Suzanne’ for the album. You see I sing in B flat or C flat and Tony arranged it in

the key of C, it was too hard to arrange in any other key I suppose, so we had a

sort of castrato vocal. Thankfully

we left it off the album, although I suppose it would have been a bit of a coup

to have had a Leonard Cohen song on there.

But then there was ‘Granny Takes A Trip’ which Nat Joseph had the

publishing on and I think he wanted me to record that.

Essex had the publishing on a song called ‘Morning Dew’ which was a

beautiful song and one that I really liked, but we should never have tried to

come anywhere near the original version. So

there you go. I did get a couple of rags on it and a few of my own songs so

I was quite happy with it.

ZZ: Where did you pick up ‘Hesitation Blues’?

RM: I learnt that from a guy called Gary Peterson, it

was while I was over in Paris. He’s

one of the finest acoustic guitarists I know.

He comes from California, he was in that crowd that Country Joe drew the

Fish from. He was playing in jug

and skiffle bands like the Cleanliness and Godliness Skiffle Band.

He was playing the streets – playing finger style which was not a great

idea because you don’t get much volume. When

I heard this guy play I thought, “Jesus, this is how I want to play”.

I can’t play the song like he does, he plays like the Rev Davis

himself. I’ve got what Stefan

Grossman calls the English guitar player’s approach, which is a bit raggy and

a bit skiffly.

ZZ: Who was managing you at this time?

RM: I didn’t really have a manager at this time.

My wife used to take bookings over the phone and I would go out and get

bookings sometimes. Then after a

while – I’d been pro for six months – Graham Churchill (of Essex Music)

used to take bookings for me. But

it soon became obvious that I needed someone full time, so my brother Bruce took

over. Later I got involved with Jo Lustig.

ZZ: Did the frequency of your gigs improve with the release of ‘Eight

Frames A Second’?

RM: Oh yeah! In

fact I think it amazed everybody. My

album came out at the same time as one by a guy called Bob Bunting.

His album was like the way I wanted mine to be, more freedom – less

attempt at a direction. I was

working with Bob at the Cousins down in Greek Street.

Bob sort of disappeared, my album did about two and a half thousand in

the first year. So by the end of

the first year I was working five nights a week all over the country.

ZZ: So they rushed you in to do the second album, ‘Spiral

Staircase’?

RM: Well, actually, I had a contract to do one a

year. The second one had ‘Streets

Of London’ on it. I had that

ready for the first album but I didn’t want to record it.

It’s funny but I had already gone off the song.

We had finished the second album and Gus said to me, “Look you really

must record that song, go on, just for me”.

So we went up to Regent Sound, £10 an hour, and did it there in two

takes. Then they decided we must

have that as the opening track on the album, so the song rushed around the

country in front of me and every gig I went to they asked me to sing it.

I suppose all the rest is history. It

never got to be a hit in this country, but over here it has been covered by

countless people [estimates vary between 20 and 40]; everyone down from the

usual Night Ride mob down to Val Doonican.

What can I say! I must admit

though that I haven’t heard all the versions.

It has got to the point now where I am totally objective about it.

I have changed my mind so many times about the song that when I listen to

it now it doesn’t feel like my song. I

no longer have a hard opinion about it at all.

I don’t sing it anymore. I

stopped half way through the last tour.

ZZ: Who was it dedicated to?

RM: Well, it was actually dedicated to a friend of

mine in Croydon. He got into a very

bad way. He died in a tragic

accident. That’s why when I

started singing it again I thought, “well it does still have a meaning, it’s

for this guy”. People, when they

listen to the song, think about the verses rather than the chorus, which to me

was the important thing. I have no

inclination to do it anymore. It’s

there, it’s his song. It will

always be his song. Nobody will

ever know.

ZZ: Also on that album was ‘Rizraklaru’.

What was that an anagram of?

RM: It was an anagram of rural

karzi.

You take the first and last letter and swing them round and spell the

whole thing backwards. It was called rural karzi because I was working the thing out

while I was living in a caravan down in Cornwall. A mate of mine, it was Henry actually, was out in the little

shed arrangement a hundred yards downwind from the caravan having a crap.

He was singing his head off and whistling away and I was thinking, “Oh,

what can I call it?” We got rural karzi but the tune seemed too pretty to call it

that. So I anagrammed it.

On Country Meets Folk we ran a competition giving away an album to anyone

who could work it out. One guy came up with ‘you’re all crazy’ (urr all krazi)

which I thought was very clever so we gave him an album for such a good effort.

ZZ: ‘Rizraklaru’ serves as a good example of your guitar style. You

seem to have broken away from the standard basic chord fingerings, is this

through deliberate experimentation?

RM: This is through looking for harmony.

I have no formal training whatsoever.

I know C, F, G7, D – the main chords.

If I’m looking for a harmony that doesn’t come in these I have to

find it for myself. You get odd

chord shapes arising from this. I am very flattered you noticed that. I think you have to experiment.

I am just solo with a guitar and I have to do new things otherwise it

would get boring. As I am not a

good singer, I look for things to help my voice along. I work very hard on the guitar parts to my songs, some of

them are really hard to learn. Once

you have worked it out you have to learn it, then you have to get fluent at it.

If I leave a song any length of time I have to relearn it.

ZZ: Two songs on ‘Spiral Staircase’ refer directly to your

childhood: ‘Mrs Adlam’s Angels’ and ‘Daddy’s Here’.

RM: Mrs Adlam was a teacher at Sunday School.

I chose Jesus all by myself. I

got a great deal of comfort and security in believing in Jesus and reading the

Bible. It wasn’t until I was

about … that I started questioning the existence of a God figure.

That’s when my radicalisation began I suppose.

I realised what dreadful circumstances my mother had been forced to bring

us up in and then I went off the idea of God.

‘Daddy’s Here’ is about what the song says and how I could almost

tell when he was going to be at my house. It

was a difficult song to write and it’s an impossible song to sing.

I have done it once or twice but the memories are too vivid, too painful.

It’s about my mother, my brother, and me, and our relationship when he

came and visited us.

My Side Of The Window and the Producer’s Side of the Glass

Ralph’s next album was the thought-provoking ‘My Side Of Your Window’, his

first under the management of Jo Lustig. It’s

Ralph’s favourite, but not mine despite the inclusion of the exceptional track

‘Michael In The Garden’. This

album brings us into the seventies and the singer-songwriter boom; so far the

first time all the tracks were Ralph McTell compositions except ‘Girl On A

Bicycle’, which was co-written with Gary Peterson, who was over in England at

the time gigging with his band Formerly Fat Harry.

I put it to Ralph that the album had the concept of a pacific

revolutionary.

RM: Yeah, that’s rather grand but it’s probably

true. That’s certainly how I was

feeling at the time. When you say

‘Ralph McTell’ to a lot of people they think, “Oh flowers and old girls

wandering around the streets of London and all that”, just because I don’t

stand up screaming at them. I was

brought up on a council estate, I was born right at the tail end of the war –

I grew up with ration books and so on – exactly the same situation that John

Lennon went through. He lost his

mother, I lost my father. I think

that makes a difference in your perspective, in the way you view things.

I was practically a member of the Communist party when I was at college,

but there’s Roy Harper in the clubs and I don’t think anyone could match Roy

for his angle and drive in that respect, so why bother?

Although I have a very working class background I think my audience is

predominantly middle class and I wanted them to understand what I was singing

about without me having to scream at them.

That’s how it all came about I think. Yeah, that’s a fair definition.

ZZ: ‘Michael In The Garden’ opens that album.

Now in the songbook, above ‘Michael’ it says ‘this song is not

autobiographical but there are times when I wish it was’.

Why?

RM: Anything you write you must feel and there are

times when I feel like I imagine he must feel, if not so exaggerated.

Somehow the way I wrote that song I wanted you to feel that the guy was

at peace with himself, although by our reckoning he wasn’t.

That peace must be a nice thing to have.

That’s basically what I meant by that statement.

A lot of people ask me if the song is about myself.

ZZ: Is he a child then, as he was in the ‘Camera And The Song’

production?

RM: Oh you saw that. Well, no – I wrote it deliberately ambiguously, he could be

any age. I have been in touch with

grown men who have got similar attitudes. When

I was working on building sites and factories I met a lot of strange people.

In the depths and bowels of factories you find all sorts of odd

characters working as loaders and packers, in jobs where you don’t really need

to think, but in fact you meet some amazingly intelligent people who have opted

out. They have their own things going on in their heads and if

anybody could only be bothered to talk to them they could learn a hell of a lot.

I mean my education didn’t stop when I want to the factory, I learnt

more there about people than I could have ever learned in school.

ZZ: This is also where ‘Factory Girl’ stems from.

RM: Yep, ‘Factory Girl’ is my own street.

At the back of our place you could see, in the mornings, the girls go to

work and then come back again in the evenings.

The song had been in my head for years and I finally got it recorded for

the third album.

ZZ: Have you produced anything since ‘My Side Of Your Window’?

RM: I have done a couple for Clive Palmer’s band on

CBS and Polydor, but I think that’s because they couldn’t get anybody else.

You see they’re all great pals of mine but like getting these geezers

in the studio together is a real hard one.

They’re so loose that they’re almost falling apart.

In some cases we had twenty goes to get them to get it together. I think they are lovely albums but the public don’t think

so, so bad luck to the public.

ZZ: Do you remember what those albums were called?

RM: One was called ‘Spirit of Love’ and the other

was ‘Moisha McStiff And The Tartan Lancers Of The Sacred Harp’.

Selling Ralph to the States and the Effects that had over there.

By now Ralph was an established artist in Britain and so it was decided to try

and break him in in the USA. They

put together an album of the best tracks for the last two albums, for Jo to take

to the States in order to impress an American company.

This was the ‘Revisited’ album which, unlike most composites, does

not sound like a collection of old tracks strung together.

It turned out to be a very good album.

All was not well in the States though, the album never got a release there.

Jo Lustig had sold Ralph to Paramount in the States, their distributors

over here were Famous/EMI. Paramount decided that they didn’t want to release an old

album and that they would rather wait for the next album and just keep

‘Streets Of London’ to put on it. So

Ralph was bought out of Transatlantic who were given the ‘Revisited’ album

while America awaited Ralph’s finest

album so far, ‘You Well-Meaning Brought Me Here’ which was released over

here without ‘Streets Of London’ on it.

RM: I chose the tracks, I drew up a list and

eventually they agreed, we hassled and haggled. When it was released over here I had to find an excuse to

warrant putting out the album when I was perfectly happy for the other albums to

stay. I had to find something to

say, but what could I say? If I

hadn’t found anything to say on the back I think it would have been worse.

I mean it wasn’t entirely the record company’s fault, but what I do

blame them for and did at the time, was making it a full price album.

ZZ: How much work did you do on the album?

RM: Re-recording ‘Streets Of London’ was the

beginning of my association with Danny Thompson – we had known each other

beforehand, but never worked together. The

other tracks were remixed up at Dick James Music, Gus Dudgeon came along and we

had Hookfoot. I was playing with

them on a couple of tracks, we took strings out, we double-tracked, we really

tried in every case to make a better version than the existing one.

A couple of tracks were left untouched, but they were the exceptions.

ZZ: The EMI album, ‘You Well-Meaning Brought Me Here’, had the

lyrics printed on it, was this your idea?

RM: Yes, I suppose it was. I had wanted them on before but this was my first gatefold.

Without the gatefold there wouldn’t have been room, we did actually

have lyrics inside ‘Spiral Staircase’ – they printed them up and the

packers, bless their hearts, and up the union, ‘cause I’m a union man, got

fed up with putting these inserts in so they didn’t.

Bruce [Ralph’s brother, original manager and later to become his

manager again, and also a thoroughly nice bloke] didn’t want the lyrics on the

record because he thought it would put me open to poetic criticism.

But I looked at other sleeves and saw that there was so much shit around

that I could stand reasonable comparison and at least people would see the way I

set out to write things, that I had actual rhyme schemes and that I set it out

like a piece of poetry. It took

quite a long time to get it word perfect, you wouldn’t believe how long. You know when you sing a song you get a word wrong or change

a phrase so we had to correct it all.

ZZ: Could you explain ‘Claudia’?

RM: That’s a heavy one, man.

It’s deliberately a bit obscure. It’s

two separate incidents that I married together.

Firstly the actual incident took place up North, where I was meeting some

geezers and we were talking and a guy did actually get beaten up because he was

white. In the song I’m waiting for him and he’s my friend and we

both get drunk whereas actually I knew it was inevitable he was going to get

beaten up and he was not one of my friends.

I don’t even think his name was John, but you’re allowed to do things

like that in songs.

At the same time, where I come from, I was with a bunch of so-called

revolutionaries, people who felt strongly about race and equality.

It was also the time of the Dylan songs and the civil rights movement and

all that and I met a chick from Harlem called Claudia.

She was working with the Black Panther party on their arts programme for

black kids. A lot of people think

when you say Black Panthers that you mean power and revolution, well it is

revolution but in the total sense, not just fighting and in Bobby Seal’s book

he disassociates himself from violence. Anyway,

I was talking to her one night, we had several long conversations.

In the end when we had agreed on virtually everything, she said, “But

you see you’re white and I’m black”, and I felt so brought down by that,

that it had ended like that when we had agreed on so many things.

I wrote that song as a warning to my ‘revolutionary’ friends, you see I’m

not saying I’m any different from back-bar revolutionaries, that’s what

Claudia is saying. I am just trying to make a point, it’s no good just talking

about equality, get up off your arses and do something about it.

But it doesn’t look like anybody was listening to me.

The only thing about putting the lyrics on the sleeve was that I thought people

might think I was a white racist or something, which I’m certainly not – no

way. It was a kind of a dialogue

thing. It was a very complex thing

to put down in the song that’s why I had to introduce Claudia and say where

she was from to try and throw some light on the song.

I save the fact that he’s white until the end.

You see, all through the song, I thought people would think he was a

black guy being beaten up by a bunch of white kids.

It was the other way around, that was the sort of twist at the end.

ZZ: Also on that album was ‘The Ferryman’ which was inspired by

Hermann Hesse’s ‘Siddhartha’.

RM: I think you can absorb ideas from everywhere.

Very rarely do I write about a book though.

That book was recommended to me when I was really screwed up. After the ‘My Side Of Your Window’ album I was getting

very down, very depressed, and I was friendly with a guy called Bruce Barthol,

who used to play bass with Country Joe’s band.

He’s split to come to England to join Gary Peterson’s mob. Bruce was one of the most laid back Americans I had ever met,

he was a lot younger than me but he was very cool, very relaxed.

I was talking with him one day and he said, “You should read this book,

I’ve got it in the States, I’ll get it sent over.”

Well he sent me this little paperback, because it wasn’t released over

here then. I read it slowly before sleeping every night and it used to

relax me. It really brought me out

of a very bad thing. I tried to

communicate the idea in my song. It

took me six months to write that song. The

tune I had, but the words had to be exactly right.

I left out a bit in the book and I changed the ending. I interpreted the book my way.

I still find it a very relaxing song to sing.

I was involved in a film of that by a guy called Conrad Rookes.

It was a very beautiful film, but it seems to have disappeared.

It was shown at the Berlin Film Festival but it never got a release as

far as I know. It may come out,

they used the song in it. The film

was called ‘Siddhartha’, it was filmed in India with all English-speaking

Indian actors.

ZZ: Presumably there is no soundtrack album?

RM: No, there would have been but big business got in

the way and swallowed it up. One of

the best things that came out of it was that I met an Indian musician called

Hermanta Khumah. He’s done

the music for about forty or fifty films back in India.

He came to my house with his little harmonium and he played me songs.

He told me what they were about and I was going to write translations.

If you have ever tried to write English lyrics to Indian tunes then you

understand what it was like. It was

a great experience and the rough recordings we did at my place are treasured

possessions.

ZZ: Now I think you wrote ‘Pick Up A Gun’ as a direct result of your

experiences in the army.

RM: Yeah, that was certainly written about my

experiences and also about what people say about soldiers.

I think a lot of crap goes down about soldiers, you know – blanket

condemnation. I think a little

closer inspection of the facts would reveal a lot.

It’s not one of my most coherent compositions in terms of the way it

all drops together. It took a long

time to write, but I just had to write it somehow.

I haven’t sung it live since I recorded it.

A Collector’s Item

It’s amazing really how many people have recorded an obscurity at some time.

Ralph is no exception, about eighteen months ago he recorded a single for

Famous that has appeared in record charts ever since.

ZZ: Was ‘Teacher, Teacher/Trucking Little Baby’ put out around this

time?

RM: It was never put out. Long story that one. It

was as a result of my spell at Teacher’s Training College that I wrote the

words to ‘Teacher, Teacher’. We

were going to make a single, I think. We

played Tony [Visconti] a lot of tracks and he picked those two.

I mean ‘Trucking Little Baby’ was practically my signature tune and

it still hasn’t been recorded on an album, perhaps the next one.

[He means the one after ‘Easy’.]

We did the single and I was knocked out, everybody was knocked out.

It even got as far as review copies and even the Daily Mirror liked it.

So I thought, “Jesus, man, you’ve got a single at last that is going

to be played.” But what happened

was, the BBC apparently put a block on it, they said they wouldn’t play it.

Now whether this was through politics I don’t know.

I doubt it. I think it

probably just didn’t fit in with what they thought of when they thought

‘Ralph McTell’. That’s the

biggest problem I’ve got, I got a name for one particular song and now every

song has to be like that or it doesn’t get played.

They can’t fit it into their little thing, you know.

ZZ: Is there any way you can get a copy?

RM: No, I don’t even have one myself.

If anyone has got one, I’d love to have it.

I’ll buy it back. There

probably are a few about, I think actually about twenty did get into the shops

and were sold, but I still get people asking if they can get hold of a copy,

collectors and that.

All Change, One More Time

After this Ralph split from Paramount. No

problem on the English front, EMI were doing a good job over here but Paramount

were neglecting their duties in the States.

They were wrapped up in the film industry and the success of ‘Love

Story’ and ‘The Godfather’. For

further discourse on the problems of recording for Paramount in the States see

Pete’s interview with Commander Cody (ZZ35).

Thus Ralph joined Reprise.

ZZ: Are you happy to stay with Reprise?

RM: Sure. I

didn’t want to move in the first place. It’s

a hassle meeting new people, new faces; it’s not that I mind that but the

media can be a real drag. You know,

this guy is the executive producer’s assistant, this guy’s the executive

producer’s assistant’s assistant and this guy is the promotional assistant

of the executive diddle-a-diddle-a-diddle, you know, and they’re all faces and

they change all the time. They’re

all young men who are trying to become big wheels in the media game.

After seven albums I’m getting a bit long in the tooth for all this

chopping and changing. I just want

to stay with a company who gets the records made and in the shops on time so

that I can just get on with making the music.

ZZ: They don’t pressure you in any way?

RM: No, they’re too big, too cool.

I think they’re good. I

imagine they would like two albums a year, most companies would, but I don’t

get that many songs written.

ZZ: Have you thought about recording other people’s songs?

RM: Oh, yeah, but there has been such a spate of

other people doing other people’s songs recently that it has postponed my own

want to do anybody else’s songs. I

think it is natural for a writer to want to get his own material accepted first,

but there have been so many incredible songs that I want to play.

Eventually I will get around to doing it.

I’ve got some funny choices as well.

Whether it all gets done or not I don’t know.

ZZ: Are you going to give us a preview?

RM: It would be wrong to say definitely.

I’d like to do Jackson C. Franck’s ‘Blues Run The Game’.

I like a song called ‘San Miguel’ which was done by the Kingston

Trio, Ry Cooder did an instrumental version of it – which choked me off.

I’ll say this for the guy, he’s got incredible taste because he keeps

recording stuff that I was going to do. I

love the stuff he records. There

may even be an old thirties thing, you know, one of Fats Waller because I love

that kind of stuff. We will wait

and see, I’ll try and get a few rags on it, Blind Boy Fuller stuff, maybe even

a Willie McTell track.

ZZ: The album you did make for Warners had that strange title,

‘Not…Till Tomorrow’. How did

that come about?

RM: That’s really funny man.

We had the album finished and they were all saying, ‘What are you going

to call it?’ and I was saying, ‘Hang on, and I’ll try to think of

something groovy.’ You see you

have to have an imaginative title but I couldn’t think of one.

I was sitting in Jo’s office and Paul Brown was on the phone, and they

rang and said, ‘Everything is ready, we’ve got the running order and we have

dealt with the musicians – have you got the title yet?’ and Paul had to ask

for another day, so he said, ‘Not till tomorrow’, and they went, ‘Yeah,

what a great title’. Paul was

saying, ‘Now wait a minute.’ He

turned to me and he said what they were going to call it and I said, ‘Yeah,

anything man, let’s get it over with.’

ZZ: ‘Zimmerman Blues’ opened that album and that’s another of your

obscure songs, isn’t it?

RM: Well, I think the Zimmerman blues is what all

early Dylan freaks must be feeling, not necessarily because of what Bob Dylan

has decided to do with the rest of his life and his music.

That’s entirely up to him, and I’ve enjoyed every album he has made.

I even dug the ‘Self Portrait’ one, but Dylan was the beginning and

the end of an era for a lot of people. The

Zimmerman Blues is a kind of attempt to understand what happened and to

sympathise and to point the finger and to ask a few questions.

Lines like:

“Do a concert for Angela, build a building or two.”

Now I don’t suppose Dylan ever did that but he did

the Bangla Desh concert, which is very commendable and understandable, whereas

at the same time I read somewhere – it’s a rumour, and rumours have some

sort of validity in this game, I suppose – that he was going into a building

project with Hugh Heffner and I find the two hard to equate and that kind of

confusion is the Zimmerman Blues.

“It gets harder for me and

easier for you.”

Well that’s how I would imagine him saying it:

“The more things go on, the more the media can capitalise on

radicalism, left-wingism, drop-outism, whatever you want to call it, the more

easy it becomes for you to criticise and the harder it is for me to maintain my

integrity. Look, you give me

millions of dollars, what am I supposed to do?

Invest it? Give it away? Or

what?”

ZZ: Do you find the same thing is happening to you?

RM: Yes. I

mean it could except that I don’t think I ever counted in any way, shape or

form for as much as Mr Zimmerman ever did.

I’m just a small part of things. I

think if people saw the guy who wrote ‘Streets Of London’ driving around in

a white Rolls Royce they might think along those lines, but I don’t think that

will ever happen, the most important thing for me is that I enjoy playing.

In fact, things have got just about as big as I can cope with in this

country.

ZZ: The start of ‘Barges’ and Grieg’s ‘Peer Gynt’ Suite sound

exactly the same.

RM: Absolutely correct. My wife is Norwegian so maybe I absorbed it from her,

although actually we had it at school I think.

It was one of the first classical pieces I was ever introduced to, and so

the influence obviously crept in there. John

Peel was the first one who told me that, on his ‘Top Gear’ show and I

thought, ‘Oh well I’m in good company and great minds think alike.’

It doesn’t matter, it’s only E minor to G, I mean Jesus Christ, there

must be a million tunes that go the same way, I’m sure he wouldn’t mind.

It’s out of copyright isn’t it?

ZZ: ‘Another Rain Has Fallen’ is on that album.

That’s one of your old songs, so why did it take you so long to record

it?

RM: I wanted to record that on the previous album and

wasn’t able to. I was very

pleased with that as a composition, I always wanted to write something in a

traditional vein. That’s the

nearest I’ve got to it so far. I’ve

done another song like that which isn’t recorded.

That might seem a bit odd on that album, but there are a few odd things

on that album anyway. There is

always one that stands out as a little odd.

I was very pleased with that song, the only reason I don’t do it more

often live is because I have a surfeit of mid to slow tempo numbers and I

don’t want to drag the whole evening down.

ZZ: There is something strange about the time on the single they took

from that album, ‘When I Was A Cowboy’, isn’t there?

RM: Yeah, ‘Cowboy’ is really weird, it’s not in

regular time at all. The drummer on

that was a friend of mine called Laurie Allen.

He was also in Formerly Fat Harry. A

very fine American band but too advanced for most of the public at the time I

think. They used to play everything

in odd time, so Laurie, when he heard ‘Cowboy’, was knocked out, he said,

‘Cor, that was clever’. I

didn’t even realise it was in odd time, it’s not strict 4/4.

ZZ: You split from Jo Lustig after that album, why was that?

RM: I left after my third year with him.

That’s a very difficult question to answer, I’d prefer to just say

our contract expired, and I didn’t renew, and that’s it.

ZZ: So back to Bruce?

RM: Back to Bruce, yeah. He’s my brother, he knows me very well, he knows what I

want, he knows what I want to work at, he understands all the songs that I

write, we grew up together you know. I

love him and he loves me and we’re good pals as well.

I don’t think you can get a better working relationship than that.

I’d just like

to add my thanks to Bruce. He’s

been amazingly helpful throughout this interview in many ways.

In fact, all the photographs you see here come out of his own personal

collection. The new album should be

out by the time this issue of Zig Zag hits the streets.

Ralph says he’s very happy with it.

I’ve yet to hear it, but he tells me that two of my favourite songs,

‘Maddy Dances’ – his tribute to Maddy Prior – and ‘Zig Zag Line’,

are on it. If the rest of the album

matches up to the quality of these two tracks then this album is going to be a

must for any Zig Zagger’s collection. So

I suggest you rush out to your local dealer and get him to play it to you.

What are you waiting for?

Fraser Massey

BACK TO INDEX

MUSIC

PRESS

Ralph

McTells All

Disc

2 February 1974

By Ray Fox-Cumming

Ralph McTell has just started a major 24-date British tour, which is near enough

a sell-out. Yet, although his

records sell well enough to cover their costs, he has never had either a single

or album hit. So how does he

account for his very substantial following?

“I honestly don’t know. It’s strange really. I

think a lot of my initial fans have stayed with me, but there are always

new, younger faces turning up.

The fact that I haven’t had a hit is probably my

own fault, I don’t usually get on very well in the studios.”

The trouble, apparently, is that the stony faces

behind the glass panel in the studios inhibit him and he doesn’t like

the accepted way of building up songs piecemeal.

To a certain extent he’s made things easier for himself by

cutting to a minimum the number of people in the studio at any one time

and now, whether anyone likes it or not, he insists on recording his

guitar and voice simultaneously. All

the same, he confesses, the best way of overcoming his uneasiness during

recordings is to get himself slightly sloshed beforehand.

Last September he recorded his fifth album, which

should be out late February or early March.

He pronounces himself more satisfied with it than any of his

previous efforts, but is reluctant to play me the whole thing, “because

you may hate it and if you do, you’ll be too polite to say so.”

However, after a little gentle persuasion, I get to

hear most of it and am very favourably impressed. The songs are all of a high standard and the production is

excellent. There is also one

song that stands out as an obvious single.

Ralph is normally thought of as a folk singer, “but

I’m not, I don’t sing folk songs.

I suppose I’m really a singer-songwriter, though the term seems

to be going out of fashion. I

think I’ll call myself a group,” he adds wryly.

He is also thought of as being a rather over-serious,

taciturn man. “I know,”

he agrees. “It’s an image

I somehow acquired and it’s very hard to get rid of it.

I’m not like that at all and I want to change it.

That’s why we’ve put out this clowning picture of me for the

tour publicity. I hated that

picture at first, but then I thought, ‘it’s me’, I’m like that, so

why not?”

He refers back to folk music and says, “Although I

don’t consider myself a folk singer, I don’t want you to think that

I’m knocking folk or folk clubs. I’m

very grateful to folk clubs, in the early days they provided me with

somewhere to play.”

I asked him if the very matey folk circuit was as

much alive today as it was in the mid-sixties when he was working it.

“To a lesser extent, yes. There aren’t so many clubs now and some of the old faces

have gone, but I like those people. They’re

very ordinary, down to earth people, not posers at all – but I’ve no

time for these 16-year old spotty herberts telling you what’s wrong with

the world.”

Ralph in no way gives the impression of a tortured

writer, wreaking havoc with his personal life to find experiences to write

about. He’s a happily

married man with two kids and a pleasantly easy-going personality. Does he find his fairly domestic lifestyle sufficient source

for his lyrics?

“Yes, I always write from life, but more about

feelings than events. Little

things happen that I store up and use when I want them.”

There’s talk of Ralph doing a TV series with Jake

Thackeray. “It hasn’t got

very far yet, it’s just an idea. As

far as TV’s concerned, they don’t know whether to put me on The Old Grey Whistle Test or The

Morecambe and Wise Show”.

But what form would the series take – a sort of

‘Folk on Two’ type of thing? “Oh

no, if the word folk comes into it I’m having nothing to do with it at

all.”

Well, a show a la John Denver then?

He visibly cringes.

“Good God no.

I’m not intending to start handing out kazoos to the audience!

I think it’ll work out all right.

Jake’s not the sort of person who’d do any kind of show that

I’d be unhappy with. Between

us I’m sure we’ll work it the way we want it.”

BACK TO INDEX

MUSIC

PRESS

McFibbing McTell

Spotlight Magazine 1975

By Desmond Ilford

So Ralph McTell has finally made the charts – and reached the No.

1 position too – with that nice little ditty, Streets of London.

Well, well. Times change

don’t they? It seems only

yesterday that old Ralphy sat sipping beer in Dublin’s Gresham Hotel on the

eve of his 1974 Carlton concert, telling the assembled press that he didn’t

think he’d both playing Streets of London at his show because after eight

years he was fed up with it.

As it happened, McTell did in fact do the number, as an encore at

the very end of his set, and ironically it was the best received song of the

evening.

Originally recorded by the

Johnstons, Streets of London has now

made Ralph McTell a star. On

February 22nd he kicks off his biggest concert tour of his

ten-year-old career, playing a total of 28 venues, including a major London

appearance at Drury Lane. And as a

prelude to the tour, Warner Bros will be releasing a new McTell album, entitled

oh so predictably, Streets.

Funnily enough, the chart-topping number was featured on an early

McTell set way back in the dark old days of ‘66/’67. Until late 1974, however, it was not released as a single

“for contractual reasons”, say the official hand-outs. Understandably, one cannot expect his record company to give

us the whole sordid story of how legal hassles prevented its issue until now and

that that is the real reason for McTell not wanting to feature the song anymore.

“I’d like to hear it recorded by a choral outfit,” he told me

last summer, “and then I want to forget it.”

Well forget it Mr McTell most certainly did not.

And in fact, he so much wanted the public not to forget Streets of London

that he even agreed to appear on BBC’s Top Of The Pops around Christmas time.

That did the trick. The

record zoomed up the charts, jostling for a while with top-selling Rubettes and

Status Quo and getting away umpteen thousand copies in the process.

So Ralph McTell has finally arrived. Well, you’ve got to hand it to him. He’s worked hard for his success and the people who come up

slowest are more often than not the ones who go down slowest too.

So congrats anyway, Ralph.

You’re a bit of a fibber, but you’re all

right.

BACK TO INDEX

MUSIC PRESS

Ralph McTell

A Fairytale Comes True

New Spotlight Magazine

March 13th, 1975

(Irelands National Music Teen Weekly)

JIMMY SAVILE introducing Ralph McTell for his first appearance on BBC's Top Of

The Pops said that once in a while in the entertainment business, a fairytale

comes true. The story of McTell's phenomenal success is such a fairytale. Ralph

wrote Streets of London seven years ago and it was first released on an album in

1969. Last Christmas it leapt into the single charts, shot into the No. 1 slot

for three weeks, is still selling here and in Britain, and looks set to clock up

sales in excess of 500,000 copies. It has just been released in Europe and has

already gone straight into the Top Ten in Germany and Scandinavia.

Streets Of London, at a time of economic crisis, is being considered as a

White Christmas-type standard by the European record industry. However, the

phenomenal success of Streets is not simply based on the popularity of the song, which has of course for years

been enormous throughout these isles, but on the deep rooted popularity of the

man who wrote it... Ralph McTell. And this is really what the fairytale is all

about. For the last ten years, Ralph has unconsciously built up a following so

dedicated and so big that he has reluctantly become a celebrity.

'But he is a star of a different, though,' says publicist Michael McDonagh.

'He is still a man of the people and his success is based on the relationship he

has established with his thousands of fans, taking as well as giving in his

rapport with an audience.'

McTell's latest album, hailed as his finest and most sophisticated to date,

was released only two weeks ago and has gone straight into the charts. Called Streets,

it was near completion before the idea came up of re-issuing Streets of London

as a single, but the success of the single caught everybody, including Ralph, by

surprise so the album was rush-released to include it and to take its title from it.

Paradoxically this album has not been produced by one of the internationally

famous producers like Gus Dudgeon (who produces EIton John) or Tony Visconti

(who produces David Bowie) and who both have worked on Ralph's earlier work ...

indeed both of them worked on Ralph's first record of '68 when all three of them

were beginning their careers.

Instead, McTell has chosen to produce this record himself and from the

ecstatic reviews he has been receiving over the last fortnight, it seems that he

has made a fair old fist of it. Witness what the Melody Maker said recently about Streets ... 'It's probably the most

wide ranging work to date, ambitiously reaching for fields beyond the usual

walls of the singer/songwriter. It is also brilliantly produced, nothing is

over-arranged, everything about it radiates class, as you would expect from

someone who has been filling concert halls for years'.

And if you're still not convinced, if you still think that Streets of London

is the only thing Ralph MeTell has ever or will ever come up with, you should

trot down to your record store for re-indoctrination. And you can tell them I

sent you ...

Paul Murray

BACK TO INDEX

MUSIC

PRESS

Ralph

McTell

By Graham Snow

Musicians Only 3 May 1980

Ralph McTell emerged from an eclectic background of folk, blues, ragtime

and rock’n’roll in the early Sixties to become a successful recording

and concert artist. A

fine songwriter and fluid fingerstyle guitarist, he recently talked to

Musicians Only about such diverse subjects as guitars, plastic

fingernails, scratched Gibsons and reversed polarity feedback cancelling.

“I’m

a bit of a squirrel where guitars are concerned – I actually had to stop

myself buying them at one point.”

His

collection began with a Harmony Sovereign, then a Harmony 12-string which

was traded for a 1954 Gibson J45.

The

Gibson is loud with a rare richness and warmth.

The finish was originally sunburst but it got scratched and Ralph

scraped the top off with – wait for it – a bit of broken glass!

“It’s

been refinished several times.

It remains my favourite guitar, the one I choose to use on stage.

I’ve tried other guitars.

Martins have got that lovely clarity but there’s something rather

special about the Gibson.”

Because

the Gibson kept getting damaged on its travels and no other J45 sounded

like it, Ralph had a copy made by Tom Mates that feels the same and looks

similar. The

Mates guitar is all maple, sounds remarkably like the Gibson and the

action is superb.

“He’s

a great craftsman. I

think it’s a lovely box; it’s going to become a beauty.”

Strings

on all his guitars are Guild Phospher Bronze, Light and Extra Light gauge.

“You

have to pick your strings. Players like Stefan Grossman and David Bromberg

play very hard and if they had those strings on their guitars they would

be pushing the strings off the neck.

John Renbourn on the other hand uses lighter strings.

You’ve got to work out which way you play.

I play a combination of quite light and, on the ragtime, quite

heavy. The only

guitar that can do both jobs is the Gibson.”

Ralph

also has a 1930 Gibson Kalamazoo, a 1931 Martin 00028, a Zemaitis

12-string and a custom built J200 copy.

Electric guitars include a Fender Stratocaster with Velvet Hammer

pickups, a Burns Double 6/12 string and a Denelectro Short Horn.

Ralph

originally taught himself clawhammer from the record of ‘Cocaine

Blues’ by Rambling Jack Elliott.

“I