RALPH, ALBERT & SYDNEY

TELLING TALES

Ralph McTell in conversation with John Beresford, January 2008.

Part 6: John enquires about the song lyrics that are missing from 'Time's Poems'...

|

The Klan

|

[John] …moving on to another area, then:

When ‘Time’s Poems’ came out, there were a few titles I was looking for and didn’t find. One of them, I thought, that might have turned up as an additional track on the re-releases last year, was ‘March of the Emmets’.

[Ralph] Good grief!

I thought you might say that! And, of course, the only reason I know about this is from Chris Hockenhull’s biography.

Best forgotten, that one. We found it. We found a recording of it.

Well, apparently it was a recording of it that led Nat Joseph to giving you the Transatlantic contract.

Well, it was actually somebody at Essex Music; it probably was, because they turned down my songs, but I said, “We’ll keep them in the frame”; and we recorded it one day. And the audience were just in hysterics, you know, listening. And it was only ever played once. We only played it once. Somebody happened to have a recording going in the room. And when we heard it, we heard all the people laughing and having a great time.

The actual publishers said, “Maybe we don’t like it, but they do. So perhaps we should take a bit more interest in this boy”. But we did find it, and David [Suff] has a copy. And I give you permission to get the lyric, if you want. But, when you see it, you’ll realise why I wasn’t terribly anxious to have it published.

It’s all about… it’s not politically correct… at that time… neither is ‘Winnie’s Rag’ actually – this thing about possibly being gay and not knowing where your orientation is because you’re missing your girl…

I never heard that in ‘Winnies’ Rag’!

It was just absolute toffee! I never felt that way in my life.

Gay people were sort of fair game. We didn’t hate them; they were just a bit odd and a bit camp and a bit funny. There’s a bit of a reference to, I think, gayness, in this song, but its actually about… ‘Emmet’ is the Cornish word for ‘ant’. You know all this, do you?

Well, only from Chris’s book.

|

OK. Us young bloods were considering ourselves the beat revolutionaries, having Wizz Jones open up Newquay and the Gannel River, and music, in this backwater called Cornwall, at the time.

And we were down there in the sixties and playing music and it was all… I was still single in 1966, back from Paris and having a great time, and so on. We adopted a rather patronising attitude to the poor folks who were only down there for two weeks a year, you know. I wouldn’t say patronising, it was light-hearted. It was still the sort of boarding house humour, about the bloke getting locked out because he got drunk that night, and the bloke changing on the beach with his towel falling off and showing his bum, and things.

|

|

Wizz Jones and Ralph McTell

|

|

And the little local café, called Matthew’s Café, which warranted a song on its own. It was about eighteen fat Cornish ladies moving behind a counter which was about six foot long, serving pasties and cream teas and cups of tea in little pots. It was just lovely, quaint and lovely.

And all the punters, who were there for a week or two, recognised themselves after two days.

Well, you have my permission, if you want, to get the lyric off of David, if he’s got it written down somewhere.

What else is there? I’m not aware of anything else.

OK, that’s missing [from ‘Time’s Poems]? The first song you wrote, ‘Klan’.

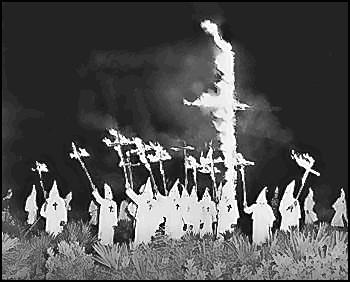

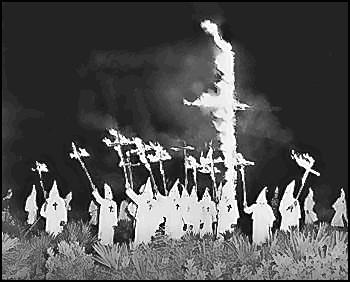

Oh, ‘The Klan’. The Klu Klux Klan. Yes, well, um...

'It looks like snow upon the hillside and it’s moving all around...'

That’s the opening verse.

|

Extract from ‘Rednecks’

by Randy Newman

Now your northern nigger's a Negro

You see he's got his dignity

Down here we're too ignorant to realize

That the North has set the nigger free

Yes he's free to be put in a cage

In Harlem in New York City

And he's free to be put in a cage in the South-Side of Chicago

And the West-Side

And he's free to be put in a cage in Hough in Cleveland

And he's free to be put in a cage in East St. Louis

And he's free to be put in a cage in Fillmore in San Francisco

And he's free to be put in a cage in Roxbury in Boston

They're gatherin' 'em up from miles around

Keepin' the niggers down

We're rednecks, we’re rednecks

And we don't know our ass from a hole in the ground

We're rednecks, we're rednecks

And we're keeping the niggers down

We are keeping the niggers down

(from the LP ‘Good Old Boys’, 1974)

|

|

You know, my sensibility towards the civil rights movement in America was one of somewhere between ‘Way Down Upon The Swanee River’ and the decency of honest working black people who were being denied basic human rights; and in total ignorance of the social scene that existed in places like Chicago, or, as Randy Newman calls it, “the cage in the South side of Chicago, the West side of Chicago”; “free to be put in a cage”, as he calls it.

But I didn’t understand, and it was only around the Watts Riots, when my girlfriend Gill, who was out there, wrote back to me about what was happening, that I began to get an understanding of the deprivation that led to extreme violence, because hitherto they had been put upon – ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’, you know, that kind of image of people not allowed a chance.

So my song about the Klan was just rather naïve and embarrassing.

But it was around the time of Dylan’s first album, and Jacqui McShee’s sister, Pam, thought it was great, because I was singing with her and a guy called Ginger Eddy in a little trio.

I played them my first song rather nervously and then rested it. I think I might have played it live a couple of times, I don’t know; but best forgotten, I think.

|

|

As you say, its probably just the first song, and it has its merits for that purpose only.

I think, probably, yeah.

I think the idea of it reminds me a little of one of Paul Simon’s earliest songs, ‘A Church is Burning’ – the same sort of idea. A little naïveté, but it makes a strong point.

|

|

Well, I think that’s what it was with me. The perversion of the burning cross - I hated that, that someone can take - I still do - take a symbol. I mean, the National Front did it with our own Union Flag. I resent that, I really resent that. And, of course, having been brought up in the Christian faith, the perversion of a burning cross in a black neighbourhood is diabolical, it’s horrible, you know. And that affected me and was part of it. It was the cross that was the principal thing in the song, I suppose, looking back.

I don’t know if I’ve got a lyric for it, anywhere, I doubt it. I probably could retrieve that one, but probably rather not.

|

|

"The perversion of the burning cross - I hated that"

|

|

Well, the only other two that I’ve heard of, that didn’t make the cut for the book, were ‘Stephenson and Watt’ - and, of course, a lovely recording of that turned up [on ‘The Journey’ box set].

Well, dear old Dave Pegg made that happen - his mandolin and mandola part on that, very nice.

Oh, right… and a song that you sang at the same time as that on the BBC in 1982...

‘Steam Train’.

‘Steam Train’.

Not really a song. I think, probably, I was desperately worried about getting these two songs… and I just sort of …it was a kind of pastiche of bluesy sort of thing about a train… and it’s gone. I don’t know; but I know someone that I think has the lyric of that, or has a recording of it - it might be Chris Hockenhull. I think he recorded it.

It will be Chris, yeah. He enthused about them in his book.

So, that’s it! That’s not bad, only four; well, only three, actually.

And, of course, since then there’s been new material - and maybe more in the coming months?

Well, I hope so.

[Go to Next Tale: Small Voice Calling]

With thanks to Ralph for sharing his time and his memories.

The text of this interview is the copyright of Leola Music Ltd, and may not be reproduced without permission.

All illustrations are the copyright of their owners or publishers and are reproduced here for information only.

|