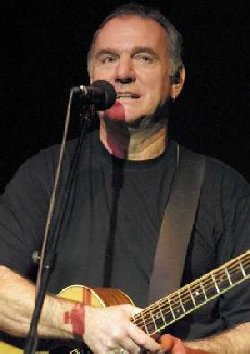

Interview with Ralph McTell

May 2003

by Paul Jenkins

RALPH, ALBERT & SYDNEY

Interview with Ralph McTell

May 2003

by Paul Jenkins

Many of you will have

read Paul Jenkins' excellent essay, 'Recurring Themes in the Songs of Ralph McTell'. This essay is now on the official Ralph McTell

web site, but Paul and Ralph kindly agreed to let me have a recent follow up

interview they did.

Andy Langran

" ....... quite one of the

most perceptive appreciation of my intentions lyrically .... I wonder how he

managed to nail everything (almost everything) so accurately ..... "

RALPH McTELL

February 2003

Paul Jenkins' Essay

POJ: The first question I have is about “Easter

Lilies”. It’s set in Oslo,

right?

RM: Yes.

POJ: And I just wasn’t exactly sure as

to the meaning of the song, whether or not it’s about a woman coming to terms

with…

RM: This song has proven to be the most

affecting song on the new album. I’m

getting correspondence about it all the time.

In Australia someone thinks it’s about teenage suicide!

Which misses the point entirely. The

song is entirely about triumph. About,

like you said, a woman coming to terms with something that is over.

Clearly coming to terms with it by celebrating a new beginning.

I heard the story surrounding the song from the woman herself.

You know in my songs I make religious references without actually

believing very strongly in anything myself, in terms of actually an organized

faith, but Easter is the Resurrection, the beginning of something.

Easter was always the beginning of something, long before it was adopted

by Christians. It’s about new

beginnings — in Norwegian the daffodil is called the Easter Lily, in England

the Easter Lily is a completely different flower. But daffodils in Britain are associated with Easter.

The daffodil sort of trumpets the shape of their little flowers and sort

of trumpets a new beginning, if you like. The

idea of her filling her room with flowers to symbolize a new beginning and

creating this atmosphere — it sounds like she’s preparing herself for a sort

of self-sacrifice, bathing, cleansing, and doing all this and that’s the

suspense in the song. It’s just

about how things really can turn like that.

It was the development of the idea, almost like a short story because

that’s the way she told it to me.

POJ: What about all the bird imagery in

the song? You’ve got the

pigeons…

RM: The mundane outside world as

personified by pigeons, you know, the ones that sit on the windowsill, watching

the world go by. She separates

herself from outside, and the idea of flight — this is entirely poetic

license; she never said any of those things — the idea of someone, the idea of

feathers on the pillow, the birds outside, almost looking down on your

situation, suspended between

reality and fantasy. She’s in

another world, watching herself almost. The

cigarette smoke is drifting like she feels herself to be drifting and holding on

to the pillow, and shows her feet are not really on the ground if you know what

I mean.

POJ: Yes.

RM: It was pure poetic license.

You still don’t know if she’s going to die at that point; if she’s

writing a suicide note or a good-bye note, but the fact that it’s not written,

and the torn envelope is a device really to suggest something that’s

discarded, but it also rhymes with “hope”.

POJ: Right (laughter).

And typical of your songs it’s got the optimistic ending.

RM: Yes, it would be a good way to analyze someone to ask if their cup is half full or half empty for the way you interpret that song. It’s designed to offer hope and new beginnings, and I always talk about it in a slightly abstract way, as I said I heard this story in Oslo. In fact Schweigaardsgate is actually where this woman lives. It’s the name of the gate in Oslo, and it’s actually where my wife comes from. It’s not an easy word to rhyme… (laughter), but I managed to find the water from the flowers as if she’d wrung the sadness from her hands, and she’s sitting there like the lost little girl on the bus. The whole device is designed to create the tension as to which way this story is going to go. It’s also got other imagery. There was an advert here in the 50s of a girl with a basket of wheat and eggs and stuff. She was wholesome and good and bringing home a drink called Ovaltine.

POJ: Oh, yeah, we have Ovaltine

here in the USA too.

RM: Right, well she was this

rosy-cheeked girl carrying her harvest of goodness home.

Well I had the woman in the song clutching the flowers like a stack of

wheat to her bosom as she comes out of the shop, buying far too many daffodils

to make any sense. Sitting there

hugging them on the bus home. We

have a little rhyme here - forgive me if I’m over explaining - if a buttercup

is held under the chin of a little one the reflection is supposed to tell if you

like butter.

POJ: Right.

RM: By the reflection of the yellow

light under the chin. There she is

abstractly looking outside the window, but the tram isn’t moving, the city is

moving around her. Again she’s

like the little girl; the daffodils reflect innocently on her skin in the yellow

glow.

POJ: How interesting.

RM: It’s not often that you can

squeeze all these images together, but I was so taken with it and I know this

woman’s history. I was just

aghast at her way of dealing with it – she told the story very quickly and

succinctly, but it was this daffodil image and the candles and so forth. I was just aghast and I felt like saying it was a noble thing

to seek poetry in a mad world. And

this was a poetic thing going on. I

just thought this is a poetic moment this woman is creating for herself and then

I took it and created the story around that.

I took her story as a lynchpin to make a creative work.

I mean she probably didn’t take the tram, but the tram itself puts you

in a time and place, it’s noisy, rattly, it’s impersonal.

She probably bought the flowers, put them in a car and drove home.

I took the end bit and worked backwards to create the story, with an idea

in mind, which was resurrection, triumph, new beginnings out of a deep sadness.

And it has affected people very much in the way I intended.

“What happens to her?” people want to know.

I don’t like things that are very cut and dried.

I think those things don’t bear repetition. And I’d like to think the songs are played several times.

And many of them I hope are multi-layered.

POJ: Yeah, I certainly think you succeed

in that. I’ll ask you next about

“The Setting”.

RM: Much of Ireland’s culture and music is to do with Ireland’s subjugated state, as an outpost of Britain and being ruled by them. The songs reflect the sadness and also the paradox, the great joy of individual Irishness and then in later years the songs that have survived are about emigration, pain at leaving and so on. First of all, I would never have written the song if I hadn’t been lucky enough to find that tune. I just love this tune, and I’m so pleased that I found it just by playing the guitar. Tunes are inside the guitar, and it’s just up to you to coax them out. I don’t wake up with melodies in my head, only once did I do that, and when I’d finished it I realized I’d rewritten “Gasoline Alley” (laughter). It was a descending progression of chords that revealed the melody, as the Reverend Gary Davis would say. I had this idea — I’d just been reading some short stories by Sean O’Faolain 1. I realized at one point I was learning not about the central character in the story but about somebody else, I don’t know whether it was his intention to do that, but I was learning about this other character. Sort of like when you’re finding out about Orson Welles in “The Third Man”, but you’re finding out about him through other actors and you don’t even see him until the end of the film. But in this case the guy is left behind. I just became intrigued by his unexplained history. He’d been away, and his story was the one yet to be told. And he was seeing his sister off on her adventure and nothing aided or assisted the sadness that he felt because everything was against him. She’s about to embark on her emigration, her journey, and the song is about how he manages to turn the situation around so that it reflects mood and place. You’re wondering who he was, what was his story and that’s what I think is the song.

The thing is I would love for “The Setting” to have been a song the Irish people picked up on, but sadly they just see it as another song about emigration, and I suppose indirectly it is, but it’s really about a moment, just a few moments where the guy slowly brings the situation round to reflect the darkness that he feels about her going and her expectations, hopes and dreams or whatever it might be. The real thing is the way the tune and the story come together. In fact at the end I felt rather cross at myself at “emigration, the curse of a nation”, I mean, it’s true but it’s rather overegging the pudding. I wish I could have got out of it a different way. I set myself an almost Victorian rhyme scheme in verse one which was really hard to sustain throughout the rest of the song. But I abandoned the discipline for the sake of the song. That is, I didn’t want the form to dominate the theme. Too much rigidity might compromise the depth of feeling.

POJ: I think you’ve won the Irish over

with “From Clare to Here” so I wouldn’t worry about that. I love the Uillean pipes at the end of “The Setting”.

It’s a nice touch and I’d hope that would endear it to lots of Irish

people.

RM: I hope so. Tom Keane, who played the pipes, is a lovely guy.

I haven’t seen him for a long time.

I bumped into him in Ireland. Unfortunately

he’s named as Frank Keane on the record.

We always have a laugh at that. I’ve

only seen him three times. Once was

to do the session and the next time was fifteen years later to tell me I’d

called him Frank instead of Tom. But

he’s forgiven me for that. By the

way, Uillean pipes is Irish for “elbow pipes.”

POJ: I didn’t know that.

Next I want to talk about the two songs “Birdman” and “Run, Johnny,

Run.” They both strike me

as sort of set down South in America, in the “Lost John” tradition or

something. I guess especially

it’s “Birdman” I'm interested in, what the inspiration for that song was.

RM: Yeah, okay, this is going to take

some time, but it’s gonna be worth it.

POJ: Okay.

RM: One of my first awarenesses of

American folk music was through an English artist called Lonnie Donnegan singing

a song called John Henry.

POJ: Right, the skiffle guy.

RM: “Rock Island Line” and all that.

I had no concept, and I had probably a rather naïve and patronizing

young way of thinking about impoverished black people and slavery and railroad

gangs and slave gangs and all that stuff.

POJ: We do too here in the United

States. It’s a very romantic kind

of thing. I think every college

student goes through a blues stage.

RM: Well, I was about 11 when the

skiffle thing burst on the British scene, and I just loved the story of John

Henry, and I managed to find out a little bit more about it over the years and

it stayed with me. During the

Industrial Revolution over here we had Luddite riots because Ned Ludd — he was

considered the village idiot — went into the factories and smashed the looms

that were putting all the men out of work.

They called the riots that followed that “The Luddite Riots”, where

men went to break up the machines because they were forced into poverty by it,

the encroachment of industrialization. In

John Henry’s case he has kind of a folky race with a steam drill and to see

how fast track can be laid. Years

later I read one of the most exciting and stimulating books I’ve read called Soledad Brother2 by George Jackson. He was a

political activist, and became very politically aware and wrote to Angela Davis,

the other black revolutionary. Do

you recall her?

POJ: Oh, yeah, and she’s mentioned in

“Zimmerman Blues”, “do a concert for Angela…”

RM: That’s correct.

Did you work that out, or did someone explain the allusion?

POJ: No, Angela Davis is still fairly

well known. I was born in 1961, so

I was at least of age to remember. I

remember exactly what she looked like; she had a big afro at the time.

RM: Well, this guy George was arrested

for a petrol station hold-up, a gas station hold-up, and it was alleged, and

probably proven as far as the courts were concerned, that George was involved in

a murder, and he was banged up in prison forever I think, and while he was in

prison he began to look at the black situation where the founding black

revolutionary activists considered all black prisoners political prisoners of

the system that had victimized them all, impoverished them all and forced them

into this kind of activity. But

George’s lessons of life really touched me very deeply.

And I was on holiday in Wales where I wrote “Nettle Wine” which is on

that same album.

POJ: Yeah.

RM: I was in the country, and the

mountains, and the beauty and George’s words.

Then the news came through

that he’d been shot in an attempted escape from prison and killed.

Now I was rocked back because though I’m not a great political activist

I began to feel very uncomfortable about the growing black awareness and

politicalization… the sixties and all that.

Medgars Evers. I felt that George was so articulate, that he was so

rational, that no system would dare kill this man.

No system would dare close his mouth.

Death is so final. Bang,

you’re gone. Was it a conspiracy?

Was he armed? Where did he get the gun?

It’s the man against the machine again and George became the new John

Henry, that’s why I threw John Henry in.

You can’t beat the system if the system wants you out.

I mean if they can shoot a president, remove a president, they can

certainly remove a black criminal. Even

those who prophesied that this would be the way that he’d go still couldn’t

believe this. I was stunned! When

I think about that album (Not Till Tomorrow) you’ve got songs of

reflection, and you’ve got very gritty songs as well, it was this kind of

crisis I was going through. And

that comes out in “Zimmerman Blues”, the paradox of Dylan the revolutionary

going into partnership with Hugh Hefner to build a 45-storey building in Chicago

and at the same time doing a free concert for Angela Davis.

What is going on in my world I wondered?

The album reflects that mood I think.

POJ: Sounds a little bit too like Bob

Dylan’s feelings for Hurricane Carter, luckily that one got resolved better,

but I would take some consolation in the fact that your songs have in part

changed the world. I’m thinking

about “Bentley and Craig”, obviously a sad story, but with a little bit of a

happy ending with the pardon.

RM: That was wonderful.

The last thing that happened was that the surviving niece, Maria, was

given some compensation. She says that song has gained a lot of publicity for the

cause.

POJ: I work as a librarian at the

College of Mount St. Joseph in Cincinnati, right across the river from Kentucky.

We teach a protest music course . . .

RM: Yes, you said that in one of your

letters.

POJ: We are going to play one of your

songs even though it’s a course on American Protest Music.

I’m going to squeeze you in there a little bit.

There’s a number of your songs I could choose, but I wanted to let you

know that for certain, that the idea that songs can change the world is being

carried on. We're really trying to impress that fact upon the kids,

especially with the current situation in Iraq.

There were a lot of songs here recently, even just circulating via e-mail

about the war. But let me ask you

really quickly. You seem like

you’re such a student of history, I’m thinking of songs like “Red and

Gold”, “Maginot Waltz”, “England 1914”, I wanted to ask you that since

you’ve had kids who have gone through the English school system whether or not

the English youth are ignoring history the way young Americans are.

We’re always appalled in this class.

There are many historical references in the songs, and you need to

understand them in order to understand the songs of protest.

Anyway many times the people won’t know the reference, for example, in

one song when Herbert Hoover was referenced in a song in terms of

“Hooverville” in the Depression we asked the kids who Hoover was and they

thought it was J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI director in the 60s.

RM: Good Lord.

POJ: It gets pretty discouraging, so

I’m hoping you can console me by telling me that the English are remembering

history more than the Americans are.

RM: I wish I could say that was true.

My own children went through the state system which is the free education

system. I suppose I could have sent

them through a private education, but I believe in an egalitarian society, far

away as it may be in this country, and they went through the normal state

system. My oldest son is incredibly

knowledgeable about history, it’s a sort of a side hobby of his.

He was born in 1967, so he’s nearly as old as you.

He often picks me off on things. The

history that the kids get taught is, in my mind, fairly basic at the moment

because I believe, perhaps wrongly, that there’s been a lowering in the

standards in the country in an effort to impress the voters, that more and more

university students are being created. I

certainly think that the ordinary level exams that we took at 16 that prepared

us for our examinations, for our college entrance at 18 have been lowered to a

ridiculous amount. I just scraped

past it on an ordinary level. It

was a very complex period of history, we did sort of the Great Reform Age from

the American Revolution until 1914. That

was our study period. Incredibly

condensed. So much happened, so

much was going on in the world and I couldn’t cope with the dates and that

stuff. But history’s always been

a bit of a hobby. But I can’t

honestly say, but I think that historical references would be lost on 90% of the

kids that go to school in Britain, and that’s very sad.

POJ: Yeah.

RM: But that’s just my opinion.

The teachers and the lecturers and the government would say that I was

wrong. I feel you have to wait

until you go to college and get into professional life before you really find

out about it.

POJ: I wanted to ask you if you feel

like there’s one of your songs you were expecting big things from that

hasn’t received its due?

RM: ALL OF THEM! (laughter).

A lot of people dismiss what I call natural musicians who wake up in the

morning and can write a song and it appears very facile.

Paul McCartney is SUPREMELY gifted.

I put him with Cole Porter, George Gershwin, some of the great musical

composers. My love of the blues,

isn’t the format of the blues, so much as the guitar playing.

I LOVE the guitar playing in the old country blues!

And I love jazz, and I’m deeply envious of what I call natural

musicians like Jimi Hendrix. The

guitar was an extension of his mind. And

I could study until the seas run dry, and I would never have what Jimi had. So I sit down with my block of stone in front of me and chip

away at it until I’ve got something. And

then I learn the guitar part and get it good - so does Bert Jansch incidentally.

I’ve watched Bert work, and I was intrigued how he was like me, he may

be more of a poet than me, and he may be a better guitarist than me, but we

approach the thing the same way. It’s

like the whole thing is learnt as a whole piece.

It doesn’t come easy to me, so when I get an idea I’m really

sensitive to overexplain things on stage, and I’ve just resisted that now

because since the advent of e-mails and so on I get a lot of people writing…

I mean the classic case was the work on Dylan Thomas where people were

writing on how they kept discovering little lines, and I’d get real joy out of

that. But as we said earlier on

repeated listenings things reveal themselves.

One day I got a card from a woman, whom I’ve since gotten to know from

Yorkshire, who told me she’d just twigged the line from The Boy With A Note about “drowsy on the cliff poised to prey upon

the right word to unlock the line.” You

swoop down and you put it in the line, and feel “yes!”

But that’s how it is with me. I’m

really slow, and I only write about five or ten songs a year these days.

And if I can’t come up with some original aspect or something or add

something new to the old stuff, you know the old sentiment, I don’t bother to

write.

POJ: Right.

RM: It gets harder.

POJ: Did you ever see Mr. Connaughton

again?

RM: Never.

I met his daughter of course.

POJ: I remember reading about that.

RM: She introduced herself as Josephine

Connaughton, and of course I called him Mr. Connaughton, and I didn’t

know who she was, and then she said we used to live upstairs to you, and I

thought “Oh, my God”. I knew

her mum had died years before, but I said “how’s your father?”

He’d been living in a place called New Addington, which is a dreadful

kind of government housing complex in Croydon, built out on those windy hills

and that’s where they made their home. If

he were alive he’d be in his mid-eighties by now.

You know the chance of me ever finding him, or finding her is pretty

slim. I pushed that, because as you

quite rightly identified it, I had this need for a father figure.

He was a very quiet man, virtually indecipherable to most people - his

accent was very strong. He was from

West Cork somewhere. Cork City.

I even tried to trace him by going to Cork and putting out a call on the

radio when I played in Ireland. But

it revealed nothing because you have to realize he came over in the early 50s.

I think he would be acutely embarrassed and bewildered at how I had

remembered him (laughter). So I

think it’s best left as… it does get to people I must say, a very profound

effect from audiences with that song.

POJ: Yeah, I’ve listened to the song

probably a hundred times now, but I get a lump in my throat every single time.

My wife kind of looks at me with this funny look (Ralph laughs) because I

had a very happy childhood, with two parents, I was very lucky, but there’s

something about that song that’s just so moving.

It’s amazing.

RM: Well, I was particularly vulnerable

that morning. Everyone had gone

away and I was on my own. I was

feeling a bit hungover, and that always sharpens my sentiments, and I literally

picked up the guitar and for once in my life the tune and the words came at the

same time. And I just literally

lifted the things I remembered. And

it went very well. I’ve dropped

it for the last couple of years, but it doesn’t usually stay out of the

repertoire very long.

POJ: One more question if I might.

It seems like temptation is a big theme in your songs too.

I’m thinking especially of “Now This Has Started”, and this is

something all men can relate to so much. I

heard that song and I’m a happily married man, but we all know what happens,

men all have roving eyes to a certain extent.

I just think you nailed it so well there.

That theme seems to go through some of your songs, “If I Don't Get Home

Soon”, “In Some Way I Loved You”, “Sweet Mystery” - this last one in a

funny sort of way. Getting at how

powerful the sex drive can be and how that sort of gets in the way of so many

other things.

RM: I always remember George Melly, an

entertainer here, who was so glad when his libido finally dropped because he

said it was like being unchained from a lunatic. (Laughter).

The whole thing about great art is the tension before the resolving,

it’s like you create a poem and you have a punch line at the end.

In the blues you sing a line and you repeat the line, you leave it tense,

then you resolve it. The whole

thing about holding things together at home and holding relationships together

is hard and you can’t always write directly about it, one has to allude to

these things. There’s this

tremendous power of sexuality, it’s all around you, and it’s coming at you

from wherever you look, so you kind of resort to poems to help relieve this, get

rid of that, you know.

POJ: Yeah.

RM: Turn reality into something else.

Without going into it too deeply that’s about all I can say about it.

It’s always there. I had

this lovely moment once. I was

fortunate enough to meet one of our great modern poets, Sir John Betjeman, have

you heard of him?

POJ: No.

RM: He was poet laureate and is probably

the most popular published poet in modern times in Britain.

He wrote lovely chugging poetry, if he wrote about a train it sounded

like a train. I do urge you to have

a look at some. Absolutely

delightful and very English in spite of his name, which is actually Dutch.

Anyway, I met him one time when he was quite an elderly man, probably 70

at the time. We were on a show

together called “Thank God It’s Sunday.”

They started off with “Mrs Adlam’s Angels” and it went on to John

exploring the activities of the British on a Sunday morning.

And he linked all the images with poetry.

Absolutely charming and so plummy and English and delightful and with a

sense of fun. We went to lunch

together during the filming, and he was admiring the waitress’s legs and how

brown they were. “Do you suppose

she’s wearing stockings?” he asked me.

Anyway, he then went on to describing this thing about at what point in

one’s life do you turn from being the dog with the roving eye to being a dirty

old man? And he came to the

conclusion that it comes down like a shutter, you know like the thing on the

back of a truck or a car where it goes “clung”.

He was dreading that moment. I’ve

got three sons, and I remember walking down the road with two of them and seeing

one young girl coming in the other direction, and I started admiring her in the

back of my mind. And there’s this

split second--it happens in a blink--where the girl will look up and take in the

entire picture, but she won’t look at you.

And there was a time when she would (laughter).

POJ: You’re right.

RM: In that split second she’s seen

his height, the color of his eyes, the breadth of his shoulders, the length of

his legs, the bulge in the crotch, I don’t know, it’s all there.

Without even looking directly she has sidelined me.

I’m not in the picture any more. It’s

one of those nice little observations, and it all came ringing true for me.

POJ: I wanted to say quickly too how

much I like “Zig Zag Line.” My

son is only five years old so we haven’t climbed a big hill yet, but it’s a

perfect metaphor for life.

RM: I was thinking of Abraham, again

it’s a biblical reference.

POJ: Oh, really.

RM: A father goes off with his son, and

he’s not sure what it is that God is going to teach him.

I loved that story. It

terrified me, that any kind of God would ask a father to kill his son.

But as I got to the top of this hill, with my heart thumping, and with my

son’s hand in mine, with total trust in me, I think I gained a tremendous

sense of relief, and I felt we learned something about each other.

POJ: Your ability to write about your

children is wonderful, and I wanted to say too, that I think your children’s

songs really are going to be remembered a long time, too, just like Woody

Guthrie’s are. Yeah, I’ll

compare you to Woody!

RM: I can’t ask for a finer

compliment. In fact, that was the

final straw that pushed me into it. I

didn’t want to do them, but my brother said to me: “Look at Woody’s

wonderful children’s songs, here’s a chance to do it for your generation.

Do it!” It was a lot of

fun.

POJ: What are you working on now?

RM: I’ve had two or three new tunes

running around in my head, and I don’t know when - I really am trying not to

think too much, I’m building at the moment.

I’ve got a house on a hill here, with my little garden, a third of an

acre. It’s on a very steep,

almost 45-degree hill, and I’ve terraced it and everything, and I’m

collecting rocks from a quarry and I’m trying to think of other things.

Music is always in my head, though, and I’ve just recently acquired a

guitar to die for, a 1963 Gibson, which is sitting right by the fire with me

now. It’s the one with the

ceramic saddle, and it sounds just beautiful.

I can’t wait to record with it. I

recorded some of Spiral Staircase with a guitar like this and foolishly

sold it and waited nearly 40 years to get another one.

Well, I haven’t waited, I just haven’t found one until now.

I paid nearly £1,500 for this thing.

POJ: Wow.

RM: And it’s worth every cent.

It’s gorgeous.

POJ: Is there a story behind the writing

of “Old Brown Dog”? I always

loved that song.

RM: It’s pure Americana.

When I was a kid moving from comics to teenage material I found a story

reproduced in strip cartoon form from a Saturday

Evening Post Norman Rockwell painting.

The story was about a boy and an old dog.

The father was ruminating on how he was going to have to take the dog

away and deal with him because he was too old and going blind.

And then the dog sees a rabbit, chases it across the field and conks out.

I was so affected by it. I

love that way of telling a story. I

got a little dog for our family, and she happened to be a brown Border Collie,

and she was sitting by me when I was at the piano.

Somebody said to me “what a depressing thought, you’ve got a pup and

you’re writing a song like this.” You

see, I like to prepare myself for the inevitable, it takes me a long time to get

used to these things. So I sort of

wrote it for her as a puppy. That

was one of the songs that got the most reaction when my first

album came out in America. I

remember DJs ringing up saying they were playing it on country stations.

I still get requests for that one. And

on the album I think that was the first time that anyone had played a lead

guitar through a Leslie Cabinet. It

was Caleb Quay. They got this bloody great Leslie Cabinet which was about as

big as an American refrigerator and they wired the guitar through.

It’s one of these things where the speakers whiz round and round and

round inside on an axis and they put stereo mikes on it.

I can now reveal that the

solo went on for about two minutes, but you can hear an edit where it goes from

an impossibly high note to a low note where they chopped a verse out.

POJ: I think Sand in Your Shoes,

and Red Sky, and National Treasure show that you’re still really

at the top of your form so I can’t wait for the next album.

RM: That’s very kind of you, Paul.

I must say on a personal note thank you very much for your perception and

your reading of my work. It was very gratifying for me to see how much you had

understood my intentions and I was very, very moved by it. I’m very grateful, and I’m sure you’ve had some

reactions to your piece.

POJ: Yeah.

There have been a number of people who have written me e-mails about it.

I think what happened is . . . Bob Dylan and Woody Guthrie are probably

my two biggest heroes - well I mean I love the Beatles too, but you just sort of

take that for granted - and I thought “this Ralph McTell guy’s amazing.

I want to learn every single one of his songs”.

So I gathered all the lyrics together - a lot of the songs were hard to

come by, especially here in America, so again John Beresford and Andy Langran

got me all these tapes and I just sort of immersed myself in your works and the

themes started to become fairly apparent, except for some of these songs that

I’ve been asking you about (laughter).

RM: There are one or two others that I

don’t know if you’ve ever heard. “Alexei”,

or “The Kentucky Miner” it was called.

POJ: No.

RM: I’ll get someone to dig that out

for you. That’s one we might talk

about some time.

POJ: Great.

RM: Back in 1967 I wrote that, and it

was considered a bit… “I don't know about that, Ralph”. I was being steered in different ways at that time, and now

it doesn’t matter anymore.

POJ: It’s so wonderful that you take

the time to actually talk to your fans. I

do not take any of this for granted. I’m

so appreciative.

RM: Oh, it’s a pleasure.

I tell you, man, when I struggle to understand what I perceive as art I

hate the ones who keep wrapping it up in mystery, and using big words and

obfuscating. If you enjoy art,

whether it’s poetry or songs or music, just tell me about it, I want to know

about it! I want to understand what

it is, why it affects me spiritually. Why

is it doing this to me? And out of

that there’s some sort of commonality and humanity and that’s what it is, or

what it should be anyway. I’m all

for demystification.

POJ: Yeah, I think the whole purpose of

life is understanding life (laughter).

RM: I don’t know what else there is.

POJ: For some of us it takes longer than

others.

RM: I’m still learning.

1. Sean O’Faolain (pseudonym of John Whelan) (1900-1991) Irish short story writer.

2.

Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson (23 Sept 1941-21

Aug 1971), 1970. Author: George Jackson.

Published by Bantam Books, New York,

1972. Paperback

published by Lawrence Hill & Co. Sept 1994 Introduction by Jean Genet.

Forward by Jonathan Jackson Jr. ISBN

1-55652-230-4.

____________________________________________________________________________

back

to top